Nikolay Sterev

University of National and World Economy

Veneta Hristova

University of Veliko Tarnovo

https://doi.org/10.53656/his2025-6s-10-the

Abstract. Entrepreneurial activity manifests across diverse domains, encompassing both economic and broader societal spheres. In recent years, the significance of one particular form—social entrepreneurship – has increasingly come to the forefront, as its role and contributions to society have gained new and tangible dimensions. Although the term itself is relatively recent, the practices it reflects have existed for centuries. The social dimension of entrepreneurship has shaped entrepreneurial behavior since antiquity: Aristotle famously stated, “Noble is he who gives, not he who accumulates wealth.” However, a considerable part of entrepreneurial responsibility and contributions to society and local communities has remained overlooked and gradually forgotten. This article traces the development of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in more recent history by examining the activities of the first “spontaneous” entrepreneurs in the Ottoman Empire, progressing to the contemporary era, where social enterprises represent not merely economic entities but platforms for innovation, cooperation, and societal transformation. In a time of global challenges, social enterprises are becoming engines of change—spaces where academia and practice converge to generate sustainable solutions.

Keywords: entrepreneurship; entrepreneurial attitudes; history of entrepreneurship; social enterprise; social economy

1. State of the problem

In the contemporary world, where material priorities often overshadow spiritual and communal development, there is a growing discussion about a new form of social interaction: social entrepreneurship[1]. Its fundamental aim is not the maximization of profit but the generation of social value through the establishment and advancement of social enterprises. In this sense, social entrepreneurship can be viewed as an expression of a “new” social contract – one that encompasses a broad spectrum of activities oriented toward discovering and implementing sustainable solutions to significant societal challenges.

Based on contemporary theoretical perspectives, social entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurs are generally defined within broader frameworks that encompass their economic roles, institutional structures, and entrepreneurial processes. According to Authors (2006), social entrepreneurship can be characterized as:

– An innovative activity that creates social value, emerging within or among non-profit and public sector entities.

– A set of institutional practices that combine the pursuit of financial objectives with the promotion of sustainable values.

– A process involving the identification of a specific social problem and its targeted solution; the evaluation of social impact, business model functionality, and organizational sustainability; and the creation of a socially oriented, profit-seeking or business-oriented, non-profit enterprise pursuing this dual mission.

– An innovative use of resource combinations directed toward pursuing opportunities aimed at developing organizations and/or practices that create or sustainably generate social benefits.

Despite its growing popularity in recent years, the concept of social entrepreneurship remains conceptually ambiguous, particularly concerning the definition of a “social entrepreneur” and the nature of their activities. J. Dees (2001) provides one of the most frequently cited definitions, describing the social entrepreneur as an agent of change within the social sector who:

– Embraces a mission to create and sustain social value (rather than merely personal value).

– Identifies and relentlessly pursues new opportunities that advance this mission.

– Engages in continuous innovation, adaptation, and learning.

– Acts boldly without being constrained by currently available resources.

– Maintains transparency and accountability to society regarding the outcomes achieved.

Social entrepreneurs establish, operate, and expand social enterprises and socially responsible business organizations that generate social benefits through their activities. Social entrepreneurship begins with recognizing a social opportunity, which is then transformed into a social enterprise that mobilizes the necessary resources to address socially significant goals (Bornstein & Davis 2010).

Traditional entrepreneurship primarily focuses on profit, business growth, and financial sustainability. Its goal is to create products or services to be sold in the market, maximizing revenue to increase market share and competitiveness. In contrast, social entrepreneurship centers on addressing significant social or environmental challenges. It aims to reduce inequalities, protect the environment, support communities effectively, and drive social change. The emphasis is on long-term societal benefits, supported by a business model that ensures financial sustainability, where profit is not the primary objective.

Despite increasing academic and practical interest over the past decades, the historical evolution of social entrepreneurship remains under-researched and is often presented in a fragmented manner. Existing studies typically focus on contemporary models, overlooking the deep cultural, economic, and institutional roots that have shaped today’s concepts. This gap presents several notable challenges:

– Historical amnesia: The absence of systematic research on early forms of social entrepreneurship—such as waqfs in the Ottoman Empire or charitable guilds in Europe—limits our understanding of how the social mission emerged within economic practices.

– Conceptual inconsistency: The term is used with varying meanings across different contexts, ranging from NGOs engaged in business activities to start-ups with explicit social objectives, which complicates historical traceability.

– Insufficient interdisciplinarity: Studies often focus primarily on economics and management, while historical, sociological, and cultural dimensions remain underexplored.

– There is a weak linkage between the past and present: contemporary academic entrepreneurship and innovation centers are rarely analyzed as extensions of earlier forms of social engagement, which disrupts continuity in the historical narrative.

These issues underscore the need for a historically informed, interdisciplinary approach that links past practices with current models, facilitating a more holistic understanding of social entrepreneurship as a phenomenon with deep-rooted origins and dynamic development.

Therefore, this paper adopts an approach that combines historical analysis with a comparative evaluation of modern social entrepreneurial practices. The central thesis posits that the Bulgarian population has been inherently entrepreneurial and socially oriented—an observation that helps explain the country’s economic successes up to the Second World War. However, subsequent processes of socialization have significantly constrained entrepreneurial initiative, resulting in the current “entrepreneurship crisis” in Bulgaria.

2. Entrepreneurship before the Liberation

To uncover the historical roots of social entrepreneurship, it is essential to examine the major stages in the economic history of Bulgarian society. This approach is necessary due to the historically separation imposed between human beings and economic activity. From the 16th to the 18th century, the modern enterprise emerged as the institutional embodiment of entrepreneurship, elevating the entrepreneurial role of the individual[2]. Only in the past decade, supported by advances in the social sciences and leadership studies, has economics once again embraced the understanding of the individual as central to the entrepreneurial process.

This philosophical shift reconnects us with Aristotle’s classical definition of “oikonomia” (economy) as the art of managing household activities for the benefit of the family unit. For nearly two millennia thereafter, economic knowledge focused on the individual as the center of economic organization, addressing the fundamental question of how to increase agricultural output given limited household land (see Dobrev 1936, 1941). As economic thought evolved, this “art of the economy” became integrated into the art of education and, by the 15th to 16th centuries, laid the foundations for economic education, aimed at mastering economic skills[3].

During the European accumulation of capital, interest in the professional and personal development of entrepreneurs increased. Numerous works in the 17th and 18th centuries legitimized the merchant as a figure of economic and social progress, emphasizing personal expertise and business ethics. Notable examples include Jacques Savary (1675), Richard Cantillon (1755), G. G. Lodovici (1752 – 1756), J. H. Jung (1785), and J. M. Leach (1806 – 1822) (see Dobrev 1936, 1941).

Penetration of Entrepreneurial Culture into Bulgarian Lands

European concepts of the merchant-entrepreneur gradually permeated the Bulgarian territories under Ottoman rule. Although interpretations vary within Bulgarian historiography, there is a consensus that the expansion of market relations in the Ottoman Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries acted as a significant catalyst for economic development, promoting growth in crafts, proto-industrial manufacturing, and agriculture (Naydenov 2020; Pascaleva 1966).

According to Roussev (2023), Bulgarian perceptions of entrepreneurs began to shift during the 17th and 18th centuries, influenced by privileges granted in 1430 to Ragusan (Dubrovnik) merchants, which enabled them to trade freely across the Empire. Pascaleva (1958) further notes that by the 1760s and 1770s, a distinct class of Bulgarian merchants had emerged, originating from prosperous craftsmen, tax farmers, and traders. They facilitated the export of local products to European markets and the import of Western goods into Bulgarian regions (Naydenov 2025).

A decisive transformation occurred in the 19th century as a result of agrarian reforms and early industrialization efforts within the Empire. Notable examples include:

– The first textile factory in Sliven (1834).

– The Gümüsgérdan factory in Dermendere, Plovdiv region (1847 – 1848).

– The silk manufactory established by Bonal in Stara Zagora (1858).

– The gabardine production workshop of Ivan Kalpazanov in Gabrovo (1860).

– The enterprise of D. Vikenti and St. Karagyozov in Tarnovo and Gabrovo, specializing in silk, spirits, and flour (1861).

– The State Printing House in Rousse (1865) (see Roussev 2016).

Entrepreneurial development also benefited from the establishment of trading houses—such as the Puliev-Georgiev Company – and from major trade fairs, including Uzundzhovo, Sliven, Eskidzhumaya, as well as the Bucharest and Galati markets (Koev 2005).

The Social Roots of Bulgarian Entrepreneurship

A comprehensive historical account would be incomplete without recognizing the humanitarian dimension of entrepreneurship. However, the term the practice of socially driven entrepreneurial behavior has deep historical roots.

Western Europe

Guilds supported their members and their families by providing aid to widows, orphans, and the sick.

Industrial reformers such as Robert Owen pioneered workers’ rights, education, and social welfare – precursors to the modern social enterprise.

Ottoman Empire

The waqf system institutionalized social responsibility by financing hospitals, schools, public kitchens, roads, infrastructure, and, more generally, activities beneficial to society (Atanasov 2024). Although waqfs failed to become engines of economic entrepreneurship due to their principle of immutability – rendering them inflexible in the face of rapidly changing economic conditions – their charitable mission, which formed the foundation of social responsibility embraced by entrepreneurs of the time, should not be overlooked (History of Bulgarian Entrepreneurship, 2022; Penchev 2022, pp. 45 – 49).

These foundations exemplify a sustainable social economy model grounded in long-term public benefit. At the same time, “spontaneous” entrepreneurs[4]—craftsmen, merchants, and local leaders – independently initiated projects that:

– Created employment opportunities.

– Supported disadvantaged groups.

– Funded education and cultural activities.

Early prototypes of modern social enterprises and entrepreneurs during the Revival period include Revival community centers, guild organizations, charitable foundations (including women’s charitable societies), trade-donation initiatives, and more (Atanasov 2023; Popova 2015; Todorova 1994). Through their diverse activities, they established a model for transferring private capital to projects serving public and social interests, which aligns with the fundamental principles of social investment. Prominent figures[5] include Hadji Hristo Rachkov, Kanyo and Genyo Sakhatchiyski, Stancho Arnaudov and his sons, Hadji Gyoka Pavlov, Tsvyatko Radoslavov, the Krustich brothers, the Georgiev brothers and their relatives, the Pulievs, Hristo P. Tapchileshtov, Ivan Grozev, Ivan Kalpazanov, Stefan Grozev, among others (Roussev 2023). These individuals played a significant role in shaping the Bulgarian bourgeois class (Ivanov 1994), modernizing the economy while reinforcing strong communal values—a defining characteristic of Bulgarian social entrepreneurship.

3. Development of Bulgarian Entrepreneurship after Liberation

Following Bulgaria’s liberation from Ottoman rule, capitalist relations were able to advance more rapidly. Analyses by Bulgarian economic historians indicate that by the late 19th century, the country experienced an initial phase of capital accumulation, driven by moneylending, trade, and speculation involving former Ottoman lands. Despite extremely unfavorable initial conditions – such as factory closures and destruction following the Russo-Turkish War, and the withdrawal of the Ottoman administration, which had been a major consumer – the Bulgarian state emerged as the primary driver of industrialization through protectionist policies (Ivanov 1994).

A significant milestone was the adoption of the Law for the Encouragement of Domestic Industry in 1894. As a result:

– In 1894, 72 enterprises were employing 3,027 people.

– In 1912, 389 enterprises were employing 15,560 people.

Industrial diversification increased: light industries based on agricultural inputs remained dominant, but extractive industries also expanded. Additionally, at the beginning of the 20th century, cooperatives were the primary form of modern social enterprise in England and Italy. In America, charitable institutions were established to invest funds in various social causes, including environmental protection. These institutions were created to benefit universities, hospitals, parks, libraries, churches, and other socially significant organizations that promoted the idea of giving to support society as a whole (Kisiova 2025).

Following the world trends, after the Liberation in 1878, social activities in Bulgaria became institutionalized through the growth of the cooperative movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Various forms of cooperatives – credit, consumer, agricultural, and production – developed into structured organizations that promoted mutual support, fair working conditions, and economic protection for vulnerable groups. These cooperatives represent the closest historical analogues to modern social enterprises in the European context (Stoyanov 2006). It is also important to highlight the activities of women’s charitable societies and public organizations, which combined social services provided in orphanages, schools, and hospitals with production activities and training (Dimitrova 2009). Additionally, the tradition of industrialist-philanthropists investing in socially beneficial causes was firmly established (Petkova 2018).

Accelerated Industrial Development Between the World Wars

At the beginning of the 20th century, the shift from small-scale crafts to machine-based production was nearing completion. Many traditional crafts began to decline, causing numerous craftsmen to lose their livelihoods and migrate to towns in search of employment. This migration, in turn, stimulated the growing demand for industrial goods. Additionally, a significant portion of the rural population became impoverished during the agrarian crisis at the end of the 19th century and moved to cities, thereby contributing to the formation of the emerging industrial working class.

These processes coincided with a shift in economic thought that moved the individual entrepreneur away from the center of economic analysis. In Britain, Alfred Marshall codified the of industrial economics, institutionalizing enterprises – not individuals – as the primary competitors in the market system (Marshall 1961). Consequently, profits and market efficiency became increasingly detached from the fulfilment of social needs (Ruffener 1935).

This upward trend is evident in Bulgaria, particularly after World War I. By 1934:

– 3,815 enterprises (mostly small and medium-sized)

– Employing 87,442 workers.

The expansion was facilitated by developments in the following areas:

– Energy supply

– Electrification of production.

– Improved industrial equipment.

This era also witnessed the emergence of the first non-governmental organizations supporting entrepreneurship, such as chambers of commerce and industry. Despite the disruptions caused by the global Great Depression (1929 – 1933), Bulgaria managed to sustain industrial growth even during wartime—a phenomenon historians have noted as unusual in European economic development (Ivanov 1994).

By the end of World War II, the primary characteristics of Bulgaria’s industrial entrepreneurship were:

– Predominance of light industry due to lower capital requirements.

– Small-scale enterprises (average of 26 workers per firm; approximately 110 hp engine capacity)

– Technological lag and difficulty in adopting innovations.

– Lower labor productivity compared to leading nations.

– A decline in foreign ownership in industry from 16–18% in 1931 to approximately 12% in 1941 (Berov 1974).

Overall, this period marks the first time entrepreneurial activity in Bulgaria flourished under free-market principles.

As demonstrated by the discussion thus far, although the term „social entrepreneurship“ is linked to modern economic models, Bulgarian history from the Renaissance and the post-liberation period presents a rich array of practices that fulfil the same functions: combining entrepreneurial initiative, sustainable financing, and significant social impact for the public good. These early forms laid an essential foundation for the development of the modern social economy sector in Bulgaria, despite their severely limited capacity to survive during the subsequent phase of entrepreneurial growth.

4. Entrepreneurship During Socialism

From the perspective of entrepreneurship studies, the period of the centralized planned economy (1947 – 1989) is one of the most challenging to examine. It is challenging to identify genuine entrepreneurial behavior in an environment governed by an ideology that rejects private property and restructures the economy around public ownership of the means of production.

A decisive turning point occurred with the nationalization carried out on December 23, 1947. At that time, there were:

– 4,628 enterprises

– 158,127 employees.

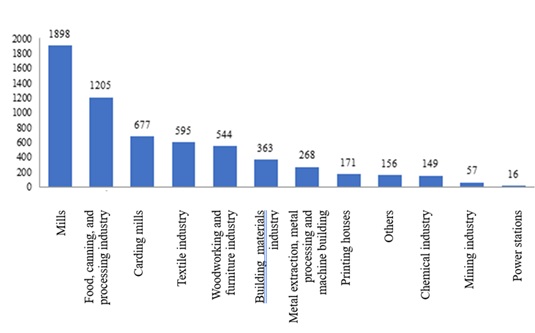

As a result of nationalization, the industrial sector underwent significant consolidation, with approximately 40% of privately established enterprises being closed (see Fig. 1). The state adopted a policy of accelerated industrialization, focusing on heavy industries such as the chemical, metallurgical, and mining sectors.

Figure 1. Distribution by Sector of Nationalised Enterprises

Source: Law on the Nationalisation of Private Industrial and Mining Enterprises (State Gazette, No. 302, 27 December 1947; amendments No. 176, 2 August 1949)

In a context where private initiative and market incentives were suppressed, the fundamental drivers of entrepreneurship—risk and profit motivation – were eliminated. Consequently, entrepreneurial activities were primarily confined to informal sectors, small craft-based practices, and cooperative associations.

There remains an ongoing scholarly debate surrounding the concept of state entrepreneurship, defined as direct state involvement in business creation (Savchenko & Shumus 1997). Although this period saw the establishment of numerous new industrial enterprises, these were driven by central planning rather than entrepreneurial initiative.

During socialism, the core principles of a free economy – such as democracy, market relations, and private economic autonomy—were replaced by a totalitarian regime and a command economy (Tutundzhiev et al. 2011). Despite the prohibition of concepts including profit, entrepreneurship, and private enterprise, the entrepreneurial spirit was not entirely extinguished; it remained latent and later served as a foundation for post-1989 renewal (Deneva 2013).

The Precursors of Entrepreneurial Revival

Historically, credit must be given to certain policy measures implemented in the 1980s that aimed to encourage the formation of small and medium-sized industrial enterprises. These initiatives contributed to the reintroduction of entrepreneurial elements into the economy. Several legal acts authorized the establishment of small production structures (Deneva 2001).

The most crucial policy shift was Decree No. 56 (11 January 1989), which enabled limited forms of private economic activity. As a result, by late 1989:

– A total of 2,596 enterprises were officially registered.

– Employing 1.58 million workers.

– Slightly over 400 were classified as small enterprises.

Table 1. Small Industrial Enterprises in Bulgaria (1982 – 1989)

| 1982 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | |

| Number of small businesses and production capacities (No.) | 188 | 305 | 381 | 432 |

| Total number of industrial enterprises (No.) | 2157 | 2340 | 2429 | 2596 |

| Proportion of small business in industry (%) | 8,71 | 13,03 | 15,69 | 16,64 |

| Proportion of the small business industrial output volume to total industrial output volume | 0,83 | 0,95 | 2,26 | 4,14 |

Source: Dimitrov 1993, pp. 83 – 95

This period ultimately laid the groundwork for the resurgence of entrepreneurial behavior, although the economic system still lacked the institutional freedoms necessary for genuine entrepreneurship to thrive.

5. The Path to

The transition to a market economy found Bulgaria with an economic structure dominated by heavy industry and large-scale agricultural cooperatives. This structure became the foundation upon which new Bulgarian entrepreneurship emerged (Manolov 1995). In the early 1990s, numerous small private enterprises were rapidly established, primarily sole proprietorships and family businesses focused on retail trade (Todorov 1997). Most new entrepreneurs either had experience in similar fields or had previously held managerial positions in state enterprises (Pachev et al. 1999).

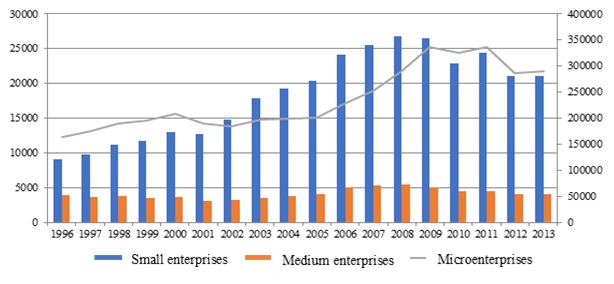

Because entrepreneurial activity is often associated with the founding of small enterprises, this sector expanded rapidly during the early years of the transition (see Fig. 2).

– 1989: approximately 2,500 enterprises

– 1995: Over 13,000

– 2004: approximately 200,000

– 2011: Over 360,000

Figure 2. Dynamics of the Number of SMEs, 1996 – 2013

Source: Author’s visualisation based on ANMSE, NSI and Yaneva, 2014

In recent decades – particularly since 2000 – the development of digital technologies has played a central role in reshaping entrepreneurial behavior. Bulgaria has followed the global transition from Internet 1.0 to Internet 4.0, resulting in:

– Widespread adoption of cloud technologies.

– Application of Big Data

– Increased use of the Internet of Things (IoT).

– Active business presence on social networks.

Expert assessments indicate that more than 40% of industrial enterprises now incorporate digital technologies into their operations.

However, despite improved framework conditions—including EU membership and integration into the Schengen Area—there has been a noticeable decline in entrepreneurial activity among Bulgarians.

One significant factor is the increasing collectivization of business activities, reflected in the renewed emphasis on the human and social dimensions of the economic system. This shift is driven by the emergence of two contemporary phenomena rooted in collaboration: co-creation and co-working.

Co-creation and co-working toward a Future of Socially Embedded Entrepreneurship

Emerging in the 1990s, co-creation has evolved beyond its original meaning. It refers to a shared space – including cyberspace – where stakeholders collaborate by combining their knowledge to generate new value. This process supports open innovation, in contrast to the traditional internal innovation model.

Success depends on skilled individuals who are willing to:

– Collaborate.

– Share ideas openly.

– Evaluate technologies and products critically.

Co-creation is also closely linked to crowdsourcing, as entrepreneurs increasingly depend on stakeholder communities to discover new solutions or enhance existing processes and technologies (Zuniga et al. 2021; Zhang & Jeong 2023; Fuchs & Schreier 2012).

Emerging in HR management in the mid-2000s, co-working refers to the creation of shared work environments where independent professionals collaborate while maintaining their autonomy (Waters-Lynch et al. 2016; Uda 2013; Lorenzo-Romero et al. 2014; Jotte et al. 2016).

By integrating co-creation and co-working within the social economy, new network-based and cooperative business structures are emerging. In these environments:

– Individuals work collaboratively to create new ideas and technologies.

– Digital tools such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), and cloud computing support innovation.

– Each person functions as a self-employed entrepreneur, contributing to collective value creation.

Thus, entrepreneurship is increasingly becoming a socially embedded activity, reflecting a broader shift toward societal impact and a collaborative economic purpose.

Academia – Business Relations: A Foundation for Future Growth

The future of Bulgarian entrepreneurship fundamentally depends on strong collaboration between universities and enterprises. Modern Open Entrepreneurship Centres aim to:

– Enhance contemporary entrepreneurial skills.

– Support student and faculty venture creation.

– Promote high value-added innovation that has social relevance.

Academic entrepreneurship builds on long-standing traditions at leading universities worldwide (Bygrave 1989; Moore 1986; Gorman et al. 1997; Vesper & McMullan 1997; Franke & Lüthje 2004). Central to this framework is entrepreneurial leadership (Sousa 2018; Nieuwenhuizen & Groenewald 2008; Nieuwenhuizen & Schachtebeck 2021), which is defined by:

– Capability to innovate.

– Creation of value through opportunity recognition.

– Personal and professional development in the learning process.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

The historical development of social entrepreneurship reveals a complex, multilayered evolution in which social mission and economic logic intertwine in various ways, depending on cultural, political, and institutional contexts. The analysis presented in this article highlights several key insights:

- Continuity and Transformation

Despite significant differences in form, the fundamental concept of public benefit has remained consistent—from waqf-based philanthropy in the Ottoman Empire to today’s university innovation ecosystems.

Over time, social entrepreneurship has evolved.

Table 2. Social entrepreneurship’s characteristics development

| Earlier Forms | Contemporary Developments |

| Charitable, religiously or morally driven initiatives | Professionalised and innovation-driven models |

| Local community support | National and global social impact |

| Informal organisation | Institutionalised structures and policies |

Source: authors summary

- Diversity of Models

A historical review confirms the absence of a universal definition of social enterprise.

Instead, there exists a spectrum.

– Non-profit organizations with income-generating activities.

– Hybrid enterprises with dual social and economic goals.

– Socially responsible commercial businesses.

- Academia’s Expanding Role

Nowadays, academic entrepreneurs and university centers for innovation play an increasingly important role in developing new solutions to societal challenges. However, they often encounter tensions between:

– Market pressures.

– Research autonomy

– Long-term social mission.

This raises a crucial question: Can social entrepreneurship stay true to its mission amid commercialization?

- Ethics and Sustainability at the Core

History demonstrates that ethics have always been fundamental to social enterprise models. However, in contemporary practice, there is a risk that ethical commitment may be overshadowed by marketing narratives.

True sustainability depends on a strong understanding of the social context, authentic stakeholder engagement, and a long-term commitment to societal change—not merely financial viability.

Generally, the history of social entrepreneurship is not merely a series of isolated initiatives. It is a human story – a testament to our enduring capacity to:

– Combine economic action with social responsibility.

– Innovate for the public good.

– Empower communities through enterprise.

From this analysis, we conclude the following:

– Social entrepreneurship has deep historical roots in both Bulgarian and global contexts.

– Contemporary models represent a natural progression of earlier traditions.

– Historical awareness can enhance contemporary practices and frameworks.

Ultimately, the future of social entrepreneurship will depend not only on technological advancements and innovative business models but also on our ability to:

– Learn from the past.

– Preserve core values.

– Adapt them to new societal realities.

Acknowledgements

The article is a result of the implementation of the project BG16RFPR002-1.014-0011 “Sustainable Development of the Centre of Excellence “Heritage BG” funded under the grant procedure No. BG16RFPR002-1.014 “Sustainable Development of Centres of Excellence and Centres of Competence, including specific infrastructures or their consortia from the National Roadmap for Research Infrastructure”.

NOTES

[1]. The main focus of traditional entrepreneurship is profit, business growth, and financial sustainability. It aims to create a product or service to be sold in the market, maximizing revenue to achieve increased market share and high competitiveness. In contrast, social entrepreneurship centers on solving significant social or environmental problems. It seeks to reduce inequalities, protect the environment, support communities effectively, and create social change. The emphasis is on long-term societal benefits, with a business model that ensures financial sustainability and where profit is not the primary goal.

[2]. Currently, research in the fields of economics and social sciences related to entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial personality, and culture is closely associated with the creation of enterprises and businesses (Roussev 2023).

[3]. In an effort to preserve economic and commercial knowledge, the Venetian Merchant Union created educational materials that revealed, to the initiated, the art of trade efficiency and the development of the merchant’s personality (or, respectively, the head of the household) along with his accounting and management skills.

[4]. In the early stages of economic development, entrepreneurs could be described as spontaneous according to their natural inclination to start businesses. Essentially, they possess internal motivation, creativity, and a desire for self-fulfilment, rather than being influenced by external factors such as government incentives or job loss. Three major periods of spontaneous entrepreneurial booms can be identified in Bulgaria: before and around the time of Ottoman liberation; between the World Wars; and at the end of the Socialist economic era transitioning into the Market economic era. Conversely, the entrepreneur starts a business based on psychological and economic motives, or through the development of entrepreneurial knowledge. The contemporary stage of entrepreneurial development, as well as some previous stages (after liberation and before the Wars, and during the mid-Socialist era), is characterized as situational, forced, or pure entrepreneurship (see IPI 2014; Shinde et al. 2022).

[5]. In Bulgarian fiction, commercial entrepreneurs were often nicknamed “chorbadzhia.” These individuals were representatives of the emerging bourgeois class—that is, wealthy people. According to Paskaleva (1962), “chorbadzhii” included merchants, livestock traders, livestock tax collectors, usurers, property owners, and tax collectors.

There are many examples of Ottoman era. Penchev (2022) found some individual Bulgarian entrepreneurs that were engaged in business activities as early as the 17th and 18th centuries such as Hristo Rachkov, Dobri Zheljazkov, Hristo Tapchileshtov, Ivan Madzharov, Evlogi and Hristo Georgievi, Hristo Danov, and others. However, it is difficult to determine the extent to which they fit the profile of a social entrepreneur (see Penchev, 2022, pp. 68–90).

References

100 godini Rusenska targovsko–industrialna kamara (dokumentalen sbornik), 1995. Ruse: IK „Nauka i praktika“ [in Bulgarian].

ATANASOV, H., 2024. Blagotvoritelni fondatsii za kreditirane. Parichnite vakafi v osmanska Bŭlgariya – razprostranenie i limiti. Izvestiya na CEHR, vol. 9, pp. 117 – 131 [in Bulgarian]. DOI: 10.61836/ICKO8237.

MAIR, J., ROBINSON, J., & HOCKERTS, K. (Eds.), 2006. Social entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 4 – 5.

BEROV, L., & DIMITROV, D. (Eds.), 1990. Razvitie na industriyata v Balgariya. Sofia: Nauka i Izkustvo. (In Bulgarian).

AVTORSKI KOLEKTIV, 2012. Industrializatsiya na Balgariya (kr. na 40-te – kr. na 50-te godini) [in Bulgarian]. http://www.bg-istoria.com/2012/12/18-40-50.html.

BEROV, L., 1974. Ikonomicheskoto razvitie na Balgariya prez vekovete. Sofia: Profizdat [in Bulgarian].

BORNSTEIN, D. & S. DAVIS. 2010. Social entrepreneurship – what everyone needs to know. Oxford university press, Part 1, pp. 1 – 41.

DEES, J. G., 1998. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Stanford University: Draft Report for

DENEVA, A., 2001. Malkiyat biznes – organizatsiya i problemi. Svishtov: SA “Tsenov”. [in Bulgarian].

DENEVA, A., 2013. Asimetriite v balgarskata industriya. Svishtov: AI “Tsenov”. ISBN – 978-954-23-0811-9. [in Bulgarian].

DIMITROV, D., 1993. Malkite predpriyatiya. Sofia: „Stopanstvo“. ISBN – 954-494-064-2. [in Bulgarian].

DIMITROV, M., 2014. Darzhavata i ikonomicheskoto razvitie na Balgariya ot osvobozhdenieto prez 1878 g. do balkanskite voyni (1879 – 1912 g.) – v tarsene na efektivnata politika. Sofiya: UI „Stopanstvo“ [in Bulgarian].

DIMITROV, M., 2014. Darzhavata i ikonomikata v Balgariya mezhdu dvete svetovni voyni (1919 – 1939). Sofiya: Universitetsko izdatelstvo „Stopanstvo“ [in Bulgarian].

DOBREV, D., 1936. Vavedenie v chastno-stopanskata nauka. Pechatnitsa Rila [in Bulgarian].

DOBREV, D., 1941. Uchenie za otdelnoto stopanstvo. Pechatnitsa Hr. Danov, №39/1941 [in Bulgarian].

FRANKE, N. & C. LUETHJE. 2004. Entrepreneurial intentions of business students: A benchmarking study. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 269 – 288. ISSN: 1793-6950. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877004000209.

GHEZZI A.; CAVALLO, A.; SANASI S. & A. RANGONE. 2022. Opening up to startup collaborations: o-pen business models and value co-creation in SMEs. Competitiveness Review, vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 40 – 61. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-04-2020-0057.

HÉBERT, R. F. & A. N. LINK. 1989. In search of the meaning of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, vol. 1, pp. 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00389915.

I.P.I. 2014. Eseta za predpriemacha. ISBN: 978-954-8624-39-8. [in Bulgarian].

IVANOV, R. et al. 1994. Stopanska istoriya na Balgariya. Svishtov: AI „Tsenov“ [in Bulgarian].

DE KONING, J. I. J. C., CRUL, M. R. M., & WEVER, R., 2016. Models of co-creation. In Proceedings of the 5th Service Design and Innovation Conference, pp. 266–278.

KISIOVA, A., 2025. Historical development and current trends in social entrepreneurship. Annual of Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski, Vol. 114–115. https://annual.uni-sofia.bg/index.php/social_work/article/view/1641/1099 [in Bulgarian].

KOEV, Y. 2005. Predpriemacheskata ideya: pregled i reinterpretatsiya. Varna: IK „Steno”, 2005. [in Bulgarian].

LAHTI M., NENONEN S. P., & E. SUTINEN, 2021. Co-working, co-learning and culture – co-creation of future tech lab in Namibia. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 40 – 58. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-01-2021-0004.

LORENZO-ROMEROA C., CONSTANTINIDES E. & A. L. BRÜNINK, 2014. Co-Creation: Customer Integration in Social Media Based Product and Service Development. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 148, pp. 383 – 396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.057.

MAIR, J., ROBINSON, J., & HOCKERTS, K. (Eds.), 2006. Social Entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN: 978-1-4039-9664-0.

MANDAVILLE, J. E. 1979. The Ottoman Waqf: A Social Instrument of Urban Development. Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 96, no. 1), pp. 37–47. ISSN: 2169-2289.

MANOLOV, K. 1995. Novoto balgarsko predpriemachestvo. Sofiya: AI „Prof. M. Drinov“ [in Bulgarian].

NAYDENOV, I., 2020. Mezhdu ikonomicheskata teoriya i stopanskata istoriya: belezhki za vlastta, pazarite i predpriemachite prez epohata na Vazrazhdaneto. Proceedings of CEHR, vol. 5, pp. 104–122. ISSN 2534-9244 (print); ISSN 2603-3526 (online). https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=919059 [in Bulgarian].

NAYDENOV, I., 2025. Problemi na stopanskata istoriya na Balgarskoto vazrazhdane v nauchnoto tvorchestvo na prof. Virzhiniya Paskaleva. Istoricheski pregled, vol. 81, kn. 3, pp. 151 – 193. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71069/IPR3.25.IN07. [in Bulgarian].

NICHOLLS, A. (Ed.). 2006. Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change. Oxford University Press. ISBN-10. 0199283877.

NIEUWENHUIZEN, C., 2009. Entrepreneurial Skills. Juta and Company Ltd. ISBN: 0702176931, 9780702176937.

PACHEV, P., KOSTOVA, S. & I. PETROV, 1999. Targovsko predpriemachestvo. Sofia: Informa-intelekt. [in Bulgarian].

PASKALEVA, V. 1958. Avstro-balgarski targovski vrazki v kraya na XVIII i nachaloto na XIX v. Istoricheski pregled, vol. 14, no.5, pp. 83 – 92. [in Bulgarian].

PASKALEVA, V., 1962. Razvitie na gradskoto stopanstvo i genezisat na balgarskata burzhoaziya. In: Paisiy Hilendarski i negovata epoha 1762 – 1962. Sofia: BAN, pp. 71 – 126. [in Bulgarian].

PENCHEV, P. 2022. Zarazhdane na bŭlgarskoto predpriemachestvo prez perioda na Vŭzrazhdaneto. in Istoria na Balgarskoto predpriemachestvo. Multiprint. ISBN: 978-619-188-946-4. https://www.sme.government.bg/uploads/2023/01/Bulg.Hist.Etrepr..pdf [in Bulgarian].

PENCHEV, P. D., 2018. The Bulgarian Revival – Myths, Achievements and Lessons. Istoriya-History, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 179 – 194. ISSN: 0861–3710 (Print), 1314–8524 (Online). [in Bulgarian].

PENCHEV, P. D., 2021. On The Political Economy of the April Uprising of 1876. Istoriya-History, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 339 – 356. DOI: 10.53656/his2021-4-1-econ. [in Bulgarian].

ROMERO, D. & MOLINA, A., 2011. Collaborative networked organisations and customer communities: Value co-creation and co- innovation in the networking era. Production Planning and Control, vol. 22, no. 5 – 6, pp. 447 – 472. ISSN (ISSN-L): 0953-7287.

RUSEV, I., 2016. Kolko i koi sa parvite fabriki v balgarskite zemi do Osvobozhdenieto (1878 g.)? Opit za izvorovedski i istoriografski analiz. Proceedings of CEHR, vol. 1, pp. 33–55. ISSN 2534-9244.

RUSEV, I. 2017. Raznoobrazie v razprostranenieto na modernata stopanska kultura na balgarite prez Vazrazhdaneto (XVIII – XIX v.). Proceedings of CEHR, vol. 2, pp. 35 – 54. ISSN 2534-9244. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=673014 [in Bulgarian].

RUSEV, I. 2023. Faktorite na ikonomicheskiya rastezh i periodizatsiyata na stopanskata istoriya na balgarite v Osmanskata imperiya (XV – XX vek). Proceedings of CEHR, vol. 8, pp. 22 – 34. DOI: 10.61836/CDSR9323. [in Bulgarian].

SAVCHENKO V. & A. SHUMUS. 1997. Fenomen gosudarstvennogo predprinimatelystva. Ros ekonom. zhurn., №1, pp. 7 – 13.

SHINDE, G., MEHRA, N., GUDI V., GIRIBABU, B., REDDY, M.G., KUMAR, S. 2022. Types of entrepreneurship: occasional situational and spontaneous. Business, Management and Economics Engineering, Vol. 20, Issue 2. ISSN: 2669-2481 / eISSN: 2669-249X.

SOUSA M. J., 2014. Entrepreneurial Skills Development. Conference Paper: AEBD 14, At Lisbon, pp. 135 – 138. ISBN: 978-960-474-394-0.

TODOROV, K., 1997. Predpriemachestvo i dreben biznes. Sofia: Martilen. ISBN – 954-538-053-2. [in Bulgarian].

TODOROV, K. 2002. Razvitie i podkrepa na dinamichnite MSP i akademichnite predpriemachi v Balgariya. Ikonomicheski izsledvaniya, vol. XI, no. 3, pp. 27 – 44. ISSN 0205-3292. https://www.iki.bas.bg/Journals/EconomicStudies/2002/2002_3/02_3_K.Todorov.pdf [in Bulgarian].

TRACEY, P., PHILLIPS, N. & HAUGH, H., 2005. Beyond Philanthropy: Community Enterprise as a Basis for Corporate Citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 327–344. ISSN 0167-4544.

TUTUNDZHIEV I., LAZAROV, I., PAVLOV, P., RUSEV I., PALANGURSKI M., & KOSTOV, A., 2011. Stopanska istoriya na Balgariya. Veliko Tarnovo: Rovita. ISBN – 978-954-8914-25-3. [in Bulgarian].

UDA, T., 2013. What is Coworking? A Theoretical Study on the Concept of Coworking. SSRN Electronic Journal, DOI:10.2139/ssrn.2937194.

VESELINCHEVA, S., 2019. Sotsialnoto predpriemachestvo kato savremenen upravlenski instrument za ustoychivo razvitie. Yugozapaden universitet „Neofit Rilski“. [in Bulgarian].

WANG, X., CHEN, F. & H. NI., 2022. The dark side of university student entrepreneurship: Exploration of Chinese universities. Front. Psychol., Vol . 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.942293.

WATERS-LYNCH, J., POTTS, J., BUTCHER, T., DODSON, J. & HURLEY, J., 2016. Coworking: A Transdisciplinary Overview. Working Paper in SSRN Electronic Journal.

YANEVA, L., 2013. Vazstanovyavat li se MSP ot ikonomicheskata kriza? Malkite i srednite predpriyatiya v Balgariya prez perioda 2008 – 2013 g. http://www.sme.government.bg/uploads/2014/12/Analiz-MSP-ik-kriza.pdf.

YORDANOV, D., 2019. Main characteristics of the modern entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship, vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 7 – 15. ISSN: 2738-7402.

YUNUS, M., 2007. Creating a World Without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism. Public Affairs. ISBN-10. 1586484931.

ZHANG X. & JEONG, E., 2023. Are co-created green initiatives more appealing than firm-created green initiatives? Investigating the effects of co-created green appeals on restaurant promotion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 108, 103361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103361.

ZUNIGA, M., BUFFEL, T., & F. ARRIETA. 2021. Analysing Co-creation and Co-production Initiatives for the Development of Age-friendly Strategies: Learning from the Three Capital Cities in the Basque Autonomous Region. Social Policy and Society, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 53 – 68. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474642100028.

DSc. Nikolay Sterev, Prof.

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8262-3241

Business Faculty

University of National and World Economy

Bulgaria

E-mail: ind.business@unwe.bg

Dr. Veneta Hristova, Prof.

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2511-2987

Business Faculty

University of Veliko Tarnovo

E-mail: vhristova@ts.uni-vt.bg

>> Download the article as a PDF file <<